Fragrant Orchid: The Story of My Early Life.

Yoshiko Yamaguchi and Sakuya Fujiwara

Originally published as Ri Koran watashi no hansei, 1987, Shinchosa.

University of Hawaii Press, 2016

Yoshiko Yamaguchi (1920-2014) recounts a wide spanning career as a Chinese singer, debuting at 13, and actress, debuting at 18, in Japan’s colony Manchukuo and Japan. Forced out of China following the end of World War II, she describes her post-war career as a Japanese entertainer and her eventual shift to journalism.

There were 1.55 million Japanese who settled Manchukuo yet few English narratives have emerged. Such narratives could help non-Japanese readers understand the circumstances and motivations of those who chose to leave Japan for an alien culture for a hoped for better life and how they met every day challenges; the timeless tale of human migration. Today, we are told that Manchukuo is a “symbol of defeat and failed colonialism” and that those who lived in Manchukuo, and other parts of the Japan’s overseas empire, were nothing more than “accessories/enablers” and “perpetrators” of a state-supported lebensraum. This message of state-sponsored failure is based on “personal testimonies,” such as the current book, Japanese films, novels and textbooks, giving the unanimous negative assessment of the “failed Manchurian project”.

Of over one and a half million stories, we have Yoshiko Yamaguchi’s. She was born in the suburbs of Fengtian (also known as Mukden), Manchuria to Japanese parents. Her father, inspired by his sinophile father, moved from Saga Prefecture to China to study Chinese language and culture. He was employed by the Southern Manchurian Railway (Mantetsu) and served as liaison with Fushun County. He also taught mandatory Chinese language and culture lessons to Mantetsu employees. A graduate of Japan Women’s University, Yoshiko’s mother moved with her parents to Fushun from Japan because of financial difficulties. Yoshiko’s parents met in Fushun and married.

Immersed in Chinese language and culture while growing up in China, Yamaguchi nonetheless retained her Japanese language and mannerisms. With respect to Chinese manners, she received gems of advice from Chinese acquaintances such as stop smiling for no apparent reason and “Stop making such deep bows as the Japanese do. We regard that as servile behavior” (p 44).

Yamaguchi acted and sang as Li Xianglan (李香蘭), meaning Fragrant Orchid, a name given to her by her Chinese godparents. In Japan, she starred as Ri Kōran, a transliteration of her Chinese name. During her career in Manchukuo, Yamaguchi was ordered to hide her Japanese ancestry and would use her given name only after the war.

Save for her closest acquaintances, most Japanese and Chinese believed that Yamaguchi was ethnic Chinese. Chinese anti-Japanese nationalists chided Yamaguchi for her questionable patriotism (p 195, 201), even calling her a traitor, for appearing in films produced by Man’ei, a major studio financed by the state of Manchukuo and Mantetsu (p 99). Man’ei’s primary mission was making film promoting Japan’s “Cooperation and Harmony among the Five Races” and “Japanese-Manchurian Friendship” (p 63).

As a student, Yamaguchi found herself in an impromptu meeting of militant Chinese students and was asked what she would do if the Japanese invaded Peking, where she lived at the time. She mumbled a noncommittal act of self-sacrifice to quell the young Chinese militants, managing to hide her “love” for both China and Japan (p 47). How patriotic.

At the end of the war, Chiang Kai-shek’s victorious gang of thugs, believing that she is a Chinese national, attempted to try Yamaguchi for treason at the end of the war. She escaped a potential death sentence when she produces her koseki as evidence of her Japanese nationality.

Yamaguchi shows readers her glittery pre-war and wartime Chinese and Japanese world of the rich and famous. She notes the Chinese elite’s frequent, casual opium use (p 43) and name drops a string of Chinese and Japanese political elites, produces, writers and high ranking military officers. She even parties with glamorous Yoshiko Kawashima, a Manchurian princess by birth, commander of the “Rehe Pacification Army” (ankoku-gun), and the “Orient’s Joan of Arc” (p 57), who sported short hair and men’s clothing. Eventually finding Kawashima’s lifestyle debauched and “disgusting” (p 58), of waking up in the afternoon and partying until dawn, Yamaguchi avoided her thereafter.

At the same time, readers catch infrequent peeks of China’s vast poverty, of slums present in every Chinese city, of rivers strewn with animal and human corpses (p. 55), and the destitute riding trains that were littered with garbage and “filled with stench” (p 32). Yamaguchi’s story is somewhat sanitized, so one will have to read elsewhere to grasp the full scale of Republican China’s appalling state of poverty, hygiene and crime in urban and well as rural areas.

Yamaguchi’s book ends with the televised 1972 signing of the Joint Communique between the Chinese Communist Party and Japan. Unable to “hold back the emotions” (p 286), she wept. What exactly was going through her mind as Japan unequivocally recognized the CCP as the “sole legal government” of China? Her China, of films, the unending glamor, debauchery and adoring Chinese audiences, evaporated long ago. Perhaps she viewed the Joint Communique as China’s complete victory over Japan—how much did she really “love” Japan?

The book ends here but not her story. Her post-war life is as interesting as her life during the Manchukuo era.

Yamaguchi left acting in the 1950s but apparently still craved an audience. As a television news reporter and anchor, one of her accomplishments was interviewing in 1973 Fusako Shigenobu, the head of the Japanese Red Army, which was responsible for a number of terrorist incidents, including the Lod Airport massacre on May 30, 1973. Two years earlier, Yamaguchi interviewed a terrorist from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, which had a hand in planning the Lod Airport massacre.

In 1974, Yamaguchi ran for office and was elected to the House of Councilors as a member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), serving in this capacity for the next 18 years. It was during her time as Councilor and LDP member that she wrote her autobiography.

As a member of the LDP’s North Korea delegation, Supreme Leader Kim Il-sung shook Yamaguchi’s hand, the Supreme Leader claiming that he saw one of her films during the war. She was a member of the Diet’s Japan-Palestinian Friendship Alliance (p xiv). In a 1989 interview, Yamaguchi stated her sympathy for the Palestine Liberation Organization, stating “I like Jews … but they have no right to occupy other people’s land.”

The LDP certainly is a “big tent” party, inviting all comers regardless of ideological persuasion, under its roof; calling the LDP a “right wing” or “nationalist” party surely reveals one’s historical ignorance.

At the end of Yamaguchi’s book, the proper conclusion one is supposed to reach is that the Manchurian colonial era was a colossal waste of Japanese lives and resources. In this vein, she has denounced her Man’ei films (p 28, 105) as “propaganda tools”. (p 89) She later did work with other studios run by anti-Japanese Chinese and less than patriotic Japanese. (p 160, 194) Indeed, despite the heavy hand of Japan in Manchukuo and censorship in Japan, the war-time world of film held their fair share of Japanese anti-government subversives and socialists. (p 90, 182)

To Yamaguchi, Japanese efforts to pull Manchuria out of feudalism are dismissed as pure exploitation. Her denunciation in fact sounds like what the CCP has been bloviating since the end of the war.

While Yamaguchi suffered material losses after being tossed out of China, she was back in show business in short order. For the rest of those who had to crawl back to Japan, there was no Hollywood happy ending.

Are there any stories about Manchukuo from regular people? There probably are, but it appears that the Government of Japan is waiting for the stories of Manchukuo survivors to quietly fade away along with the survivors themselves.

My mother was there with her parents and siblings, from first grade until they were forced out by the Reds at the end of the war. It has been a long time since then and she, like the average Japanese, stoically sit in silence.

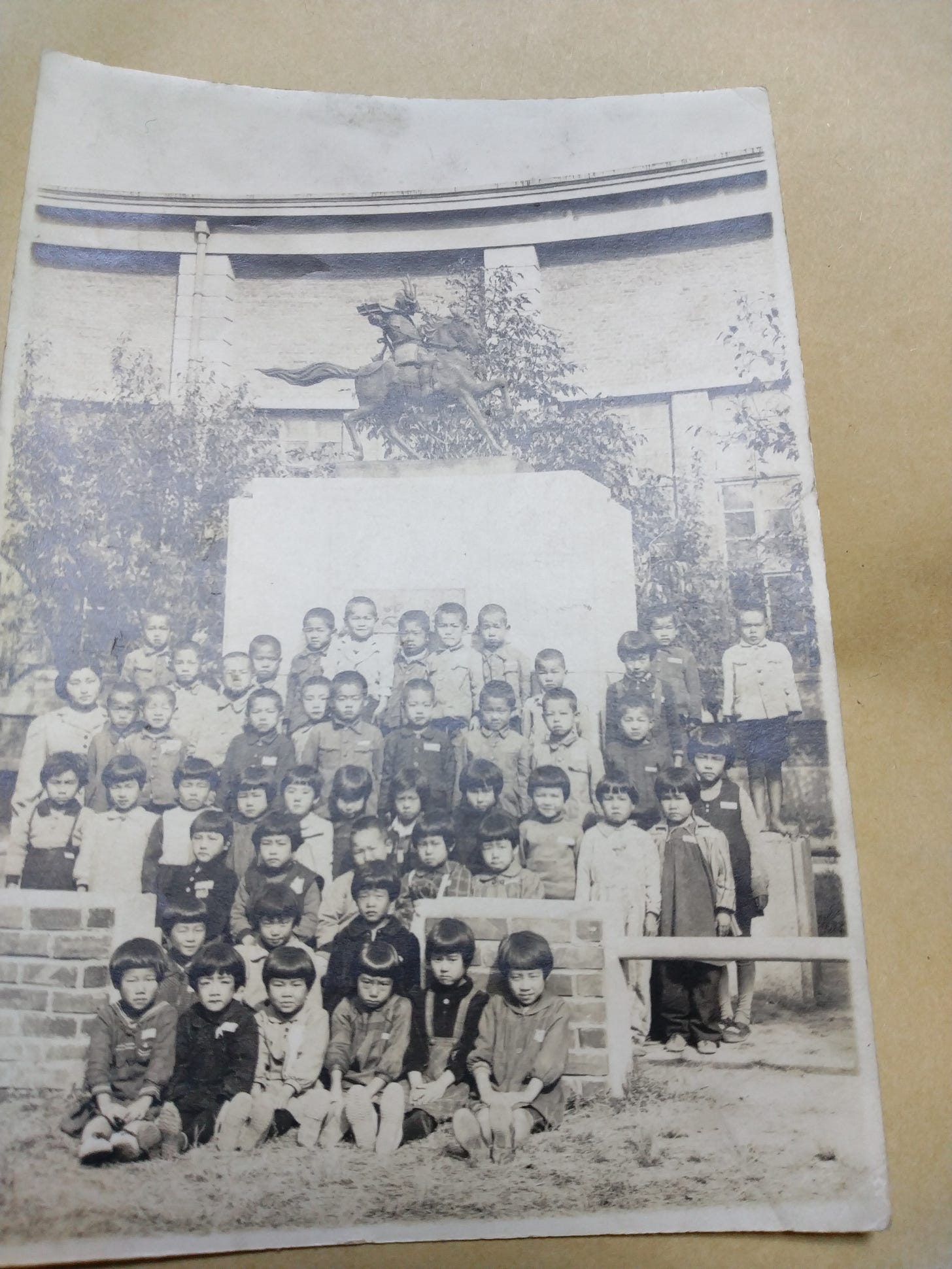

First graders, Manchukuo, 1941: My mother is the one with the rice bowel hair cut.